Percy Williams: World’s Fastest Human

February 28, 2023By Jason Beck

On February 24th, the BC Sports Hall of Fame hosted a most emotional event, righting a terrible wrong committed over 43 years ago. Replicas of Percy Williams’ 1928 Olympic gold 100m and 200m medals, the originals of which were stolen in 1980, were returned to display at the BC Sports Hall of Fame after over four decades. Several members of Percy’s extended family represented by Tracey and Brian Mead were in attendance to receive the replicas from Canadian Olympic Committee president Tricia Smith and then they in turn donated them to the BC Sports Hall of Fame. We took the opportunity to create a large display devoted to Percy’s incredible 1928 Olympic gold medal triumphs, of which these medals are the central feature.

On February 24th, the BC Sports Hall of Fame hosted a most emotional event, righting a terrible wrong committed over 43 years ago. Replicas of Percy Williams’ 1928 Olympic gold 100m and 200m medals, the originals of which were stolen in 1980, were returned to display at the BC Sports Hall of Fame after over four decades. Several members of Percy’s extended family represented by Tracey and Brian Mead were in attendance to receive the replicas from Canadian Olympic Committee president Tricia Smith and then they in turn donated them to the BC Sports Hall of Fame. We took the opportunity to create a large display devoted to Percy’s incredible 1928 Olympic gold medal triumphs, of which these medals are the central feature.

It also allowed everyone the opportunity to celebrate the remarkable career of one of Canada’s greatest Olympic athletes, ‘Peerless’ Percy Williams.

How these replica medals came to be created is an interesting story all by itself.

When the BC Sports Hall of Fame was created in 1966, Percy Williams was one of our hall’s inaugural inductees. He was also one of the very first athletes to donate memorabilia to the new hall of fame located in the BC Building at the PNE. Included amongst the large collection Percy donated from his sprinting career were his 1928 Olympic gold medals.

When the BC Sports Hall of Fame was created in 1966, Percy Williams was one of our hall’s inaugural inductees. He was also one of the very first athletes to donate memorabilia to the new hall of fame located in the BC Building at the PNE. Included amongst the large collection Percy donated from his sprinting career were his 1928 Olympic gold medals.

In January 1980, when gold prices had spiked to historic highs, a thief broke into Percy’s display case at the BC Sports Hall of Fame one night and stole 11 of his medals, including both Olympic golds. The Hall of Fame’s general manager at the time, Peter Webster, discovered the theft and immediately contacted authorities across North America and around the world including the RCMP, Interpol, and the FBI. Despite some of Percy’s other stolen medals being anonymously returned to the BC Sports Hall of Fame over a decade later, his 1928 Olympic gold medals have never been recovered.

During the Covid-19 pandemic, like many families Tracey and Brian Mead of Ontario used their extra time to research their family’s genealogy and fill in gaps in their family tree. Through talking with relative Della (Williams) Riedel, they discovered they were related to Percy Williams. Della’s first husband, Roy Williams, was Percy’s cousin. Della, who is 102 years old today, was eight years old when Percy won his gold medals in 1928. Tracey and Brian’s children lived in Vancouver, so in the summer of 2022 they flew to the West Coast and visited the BC Sports Hall of Fame. Here they saw Percy’s statue outside the Hall’s front entrance, crouched in a sprinter’s start and ready to explode down the track. They also saw his induction plaque in the Hall of Champions and artifacts of his on display. It was also then that they learned about the theft of his medals.

gaps in their family tree. Through talking with relative Della (Williams) Riedel, they discovered they were related to Percy Williams. Della’s first husband, Roy Williams, was Percy’s cousin. Della, who is 102 years old today, was eight years old when Percy won his gold medals in 1928. Tracey and Brian’s children lived in Vancouver, so in the summer of 2022 they flew to the West Coast and visited the BC Sports Hall of Fame. Here they saw Percy’s statue outside the Hall’s front entrance, crouched in a sprinter’s start and ready to explode down the track. They also saw his induction plaque in the Hall of Champions and artifacts of his on display. It was also then that they learned about the theft of his medals.

Walking back to their hotel, they decided something should be done about that. Not long after, Brian wrote to the Canadian Olympic Committee asking if replica medals could be made. Once his family’s connection to Percy was verified and the theft confirmed, the COC contacted the International Olympic Committee in Lausanne, Switzerland. Now usually this is where these types of requests end. The IOC rarely reproduces medals from past Olympics and has stuck to this policy for quite some time now. But they were so moved by the family’s story and the unique circumstances of the medals’ disappearance that they chose to make an exception. Using the same specifications employed in 1928, two gleaming gold medals were produced. Just a couple of months later, they were sent to the COC in Montreal.

When Nicholas Cartmell and I were informed of what had taken place and then that the Williams family intended to donate them to the BC Sports Hall of Fame to return them to display where all Canadians could enjoy them as Percy had always intended, we were flabbergasted. These sorts of things just don’t happen. And the fact our Hall was the beneficiary of it all, finally putting that dark moment in our history behind us, we decided we needed to bring everyone together for one presentation for two reasons. One, to recognize the generosity of Percy’s family, the COC, and IOC, who each played key roles in making this happen. And two, to shine the spotlight on Percy’s remarkable story, which most Canadians are completely unaware of.

When Nicholas Cartmell and I were informed of what had taken place and then that the Williams family intended to donate them to the BC Sports Hall of Fame to return them to display where all Canadians could enjoy them as Percy had always intended, we were flabbergasted. These sorts of things just don’t happen. And the fact our Hall was the beneficiary of it all, finally putting that dark moment in our history behind us, we decided we needed to bring everyone together for one presentation for two reasons. One, to recognize the generosity of Percy’s family, the COC, and IOC, who each played key roles in making this happen. And two, to shine the spotlight on Percy’s remarkable story, which most Canadians are completely unaware of.

We invited several people to attend who knew Percy. This included Charlotte and Victor Warren (the children of Harry Warren, one of Percy’s Canadian Olympic teammates and a close friend), Lee Wright (son of Harold Wright, another Percy’s Canadian Olympic teammates and an old friend), and Bill McNulty (member of the group who fundraised to complete Percy’s statue and author of a book on Percy).

Doug and Diane Clement shared their memories of Percy both as an inspiration to their own athletic careers and later as a supporter of the early track meets they organized which later became known as the Harry Jerome Track Classic. Doug recalled the framed photo of Percy that was displayed in King Edward High School when he was a student there and how that inspired his own athletic career.

“I would walk out of my classroom and there was Percy Williams,’ he said pointing to the actual framed photo of Percy that had once adorned the wall at King Ed and now is part of the Hall of Fame’s display devoted to him. “I later made the Canadian Olympic team in 1952 at the age of 19 too.”

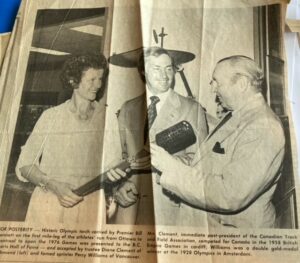

Diane recalled how at the 1976 Olympics in Montreal when she served as president of Athletics Canada she helped organize many of Canada’s greatest Olympic athletes as part of the Torch Relay, including Percy.

Diane recalled how at the 1976 Olympics in Montreal when she served as president of Athletics Canada she helped organize many of Canada’s greatest Olympic athletes as part of the Torch Relay, including Percy.

“It was such an honour and he was so gracious and so excited, you’d almost think he was running in the final of the Olympic Games,” Diane remembered. “He was so proud to be a Canadian and to carry the torch behalf of our Canadians. He was our inspiration and he’s still an inspiration to so many of our Canadian athletes.”

Tracey and Brian Mead shared some words on behalf of Percy’s extended family that had most of those in attendance misty-eyed.

“On behalf of my great aunt Della, my great uncle Roy and the rest of the Williams family, we are honoured to be able to return Percy’s gold medals back to their rightful spot at the BC Sports Hall of Fame where Percy always intended for them to be displayed for future generations to enjoy,” said Tracey Mead, her voice heavy with emotion. “What a proud and satisfying moment. This feels right.”

Tricia Smith, representing the COC and IOC, had the honour to present the medals to Tracey and Brian.

Tricia Smith, representing the COC and IOC, had the honour to present the medals to Tracey and Brian.

“I grew up in Vancouver and I cannot remember a time when I didn’t know the name Percy Williams,” Tricia said. “I knew him as a hometown hero, a champion, a person of whom we were very, very proud. There’s no doubt he had tremendous impact on sport in British Columbia and inspired many, including myself, both here in BC and across Canada. After discussions with the International Olympic Committee, a rare exception was made and an appropriate exception I would say to replace the medals. I know these Olympic medals represent only a fraction of Percy’s incredible sprinting career, but I’m certain they will help tell the inspiring story of Percy’s determination of his accomplishments and the restoration of these medals to the BC Sports Hall of Fame will allow generations of BC athletes and all British Columbians and Canadians to continue learning about Percy’s life and legacy and continue to be inspired.”

I was asked to share some words on Percy’s background and legacy, which I was honoured to do and am proud to share here in edited form:

Percy Williams.

It’s a name I believe all Canadians should immediately recognize. I truly believe ‘Peerless Percy’ is Canada’s most under-appreciated Olympic athlete of all time.

time.

When I started working here for the BC Sports Hall of Fame twenty years ago, I often began my tours right outside the Hall of Fame’s front door beside that bronze statue. I would ask groups young and old if they knew who this crouched sprinter was. It amazed me how few people could name that it was Percy Williams, born and raised right here in Vancouver.

Double Olympic gold medalist in the 100m and 200m.

British Empire Games gold medalist.

Multiple world record holder.

The World’s Fastest Human.

Percy Williams should be one of the most well-known and celebrated Canadian athletes of all time. Perhaps today’s news will help a little in shining more of the spotlight on his remarkable athletic career.

So who was Percy Williams?

So who was Percy Williams?

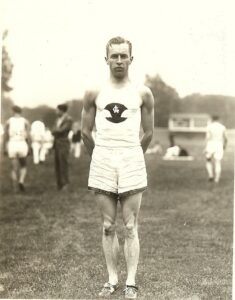

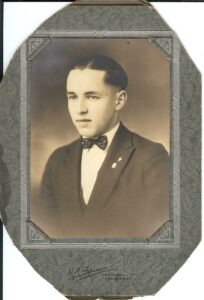

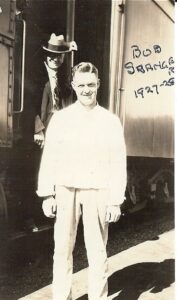

He was born here in Vancouver in 1908. As a boy he suffered from rheumatic fever, which weakened his heart. Doctors told him to take it easy and avoid strenuous physical activity. But, thank goodness, he didn’t. By the time Percy was in school, his explosive, natural speed was already obvious. He began winning races as early as age 12 while attending St Michaels University School in Victoria. Later he attended King Edward High School and the Highschool of Commerce in Vancouver. It was in high school that coach Bob Granger first saw him run and soon took on coaching him. Percy would run for the Vancouver Athletic Club locally and soon was considered one of the top sprinters in BC. He trained with other top local Vancouver sprinters who became his friends, a few of which are also inducted in our Hall of Fame like Harry Warren, Harold Wright, and Jack Harrison.

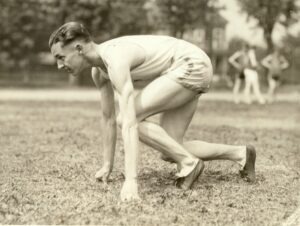

Granger was a rather unique coach, ahead of his time in some respects and a perfect fit for a talented, willing athlete in Percy. Granger had Percy practice visualization techniques before races—years before the term even existed. Because of Percy’s childhood health issues, Granger believed Percy had a limited amount of energy and focused on not wasting it whenever possible. This meant that Percy’s standard warm-up for a race involved staying in the warm locker room until the last possible moment while laying under a pile of heavy blankets warm enough to build a light sweat. Famously, days before the 1928 Olympics in Amsterdam Granger had Percy work on his starts in their hotel taking a few hard strides down the hallway outside his room and crashing into a mattress propped against the wall. Some scoffed at their techniques, but they worked.

in Percy. Granger had Percy practice visualization techniques before races—years before the term even existed. Because of Percy’s childhood health issues, Granger believed Percy had a limited amount of energy and focused on not wasting it whenever possible. This meant that Percy’s standard warm-up for a race involved staying in the warm locker room until the last possible moment while laying under a pile of heavy blankets warm enough to build a light sweat. Famously, days before the 1928 Olympics in Amsterdam Granger had Percy work on his starts in their hotel taking a few hard strides down the hallway outside his room and crashing into a mattress propped against the wall. Some scoffed at their techniques, but they worked.

The influence of Granger’s unique and innovative coaching techniques on Percy can’t be underemphasized. Late in life when asked how important Granger was to his success, Percy said, “Everything. Granger was everything.”

Physically Percy looked much different from the muscular builds we expect of most powerful sprinters today. He was only 5’6” in height and weighed a wispy 125 lbs as an adult. Jim Kearney the great Vancouver Sun sportswriter once wrote that Percy was built like a young frail fawn. To which I’d add that wasn’t a bad thing, because he also ran like one.

Physically Percy looked much different from the muscular builds we expect of most powerful sprinters today. He was only 5’6” in height and weighed a wispy 125 lbs as an adult. Jim Kearney the great Vancouver Sun sportswriter once wrote that Percy was built like a young frail fawn. To which I’d add that wasn’t a bad thing, because he also ran like one.

After Percy won the 100m and 200m at the 1928 Canadian Olympic trials in Hamilton, he earned the right to compete at the Olympics in Amsterdam. There was no money to send Granger along as his coach. Granger ended up working on a cattle boat to pay his way across the Atlantic to Europe.

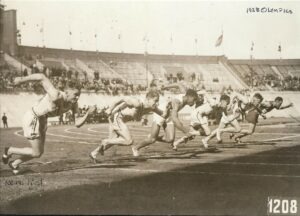

No one expected anything of the small Canadian sprinter at the Olympics, but he advanced through the heats and semifinals to the 100m final against top sprinters from the US, Britain, and Germany. Before the final, Granger’s last words to Percy were: “You’ve been here before. It’s just another Brockton Point race.”

sprinters from the US, Britain, and Germany. Before the final, Granger’s last words to Percy were: “You’ve been here before. It’s just another Brockton Point race.”

After digging his starting holes in the dirt track with his garden trowel and wearing small leather track spikes and competitor number 667 below the red maple leaf on his Canadian singlet, Percy streaked down the 100m track in Amsterdam’s Olympic Stadium in 10.8 seconds to win. Canadians in attendance and later at home upon hearing the news went wild. There had never been a victory like this by a Canadian athlete in the Olympics to this time. It was so unexpected organizers had to scramble to find a Canadian flag and music for the national anthem for the medal ceremony.

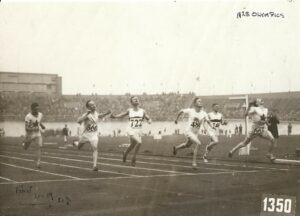

And then even more remarkably just a few days later, Percy did it again, winning the 200m final in 21.8 seconds to take his second Olympic gold medal. To say the world was shocked would be a massive understatement. No one, outside of Bob Granger, had predicted it. Many have said Percy put Vancouver on the world map for the first time that week in the summer of 1928.

And then even more remarkably just a few days later, Percy did it again, winning the 200m final in 21.8 seconds to take his second Olympic gold medal. To say the world was shocked would be a massive understatement. No one, outside of Bob Granger, had predicted it. Many have said Percy put Vancouver on the world map for the first time that week in the summer of 1928.

This was a time when Canada might bring home just a handful of medals from an Olympics during a good year. With those two victories in 1928, Percy was the first individual Olympic gold medalist from British Columbia. It was only 20 years since the first BC athletes had begun participating at the Olympic Games.

To this day, there have been only nine male athletes in history who have won the Olympic double—winning both the 100m and 200m at the same Olympics. Some of these athletes are among the most celebrated athletes in the history of world sport like American sprinters Jesse Owens and Carl Lewis, and more recently the legendary Usain Bolt, who captured the Olympic double a record three times. Percy Williams, from Vancouver, British Columbia, Canada is one of those nine, only the third athlete ever to accomplish this feat and the only Canadian to do so to this day.

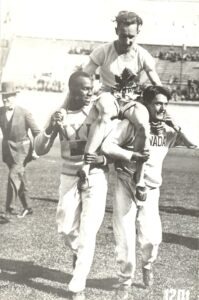

When Percy returned to Canada, he travelled across the country by train back to Vancouver, celebrated at every major city along the way and showered with gifts. In Vancouver, over 25,000 crowded the streets to honour him with the city’s largest parade in history to that time. That was over 1/6 of the city’s entire population.

Percy would later break the world record in the 100m at the 1930 Canadian Track and Field Championships in Toronto, running 10.3 seconds. His record would stand for six years until broken by the great Jesse Owens. A few weeks later Percy won the 100 yards at the inaugural British Empire Games in Hamilton in 9.9 seconds despite suffering a severe muscle tear in his left thigh thirty yards from the finish line. His leg was never the same, although he did manage to recover enough to compete at the 1932 Olympics but wasn’t able to make the final of either the 100m or 200m, although he did lead the Canadian 4x100m relay team to fourth place. After retiring following the Olympics, Percy worked in Vancouver for several decades as an insurance agent living a quiet, often reclusive life, occasionally appearing for special events locally.

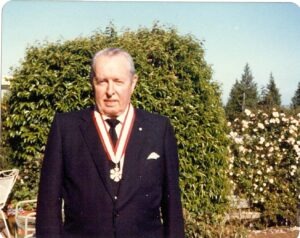

As uncomfortable as Percy was with fame and the spotlight, awards and accolades continued to be bestowed upon him throughout his life. In 1955, he was part of Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame’s inaugural induction class. In 1972, he was named Canada’s all-time greatest Olympic athlete. In 1979, he was awarded the Order of Canada. After his death in 1982, the Percy Williams Junior Public School in Scarborough, Ontario was named in his honour. In 1996, Canada Post issued a postage stamp honouring Percy.

As uncomfortable as Percy was with fame and the spotlight, awards and accolades continued to be bestowed upon him throughout his life. In 1955, he was part of Canada’s Sports Hall of Fame’s inaugural induction class. In 1972, he was named Canada’s all-time greatest Olympic athlete. In 1979, he was awarded the Order of Canada. After his death in 1982, the Percy Williams Junior Public School in Scarborough, Ontario was named in his honour. In 1996, Canada Post issued a postage stamp honouring Percy.

And Percy’s greatest legacy? It might be our Canadian flag. When trying to find a design or image that summed up Canada, George Stanley, the man tasked with creating Canada’s new flag in the mid-1960s, was inspired by none other than Percy Williams. Here’s a direct quote from Stanley:

“I was so impressed with a picture of Percy Williams winning a gold medal in the 1928 Olympics that it always stayed in my mind and inspired me when I was designing the flag. As Williams breasted the tape, you could see the large maple leaf on his jersey and there was no doubt everyone knew he was from Canada.”

was designing the flag. As Williams breasted the tape, you could see the large maple leaf on his jersey and there was no doubt everyone knew he was from Canada.”

Isn’t that amazing? This is why every Canadian should know the story of this incredible athlete.

I’d like to close with a quote from someone who knows Percy’s story probably better than anyone. Sam Hawley was a Kingston, Ontario-based writer who wrote an amazing book on Percy’s life called “I Just Ran” published in 2011 by Ronsdale Press here in Vancouver. Sam is now living in Turkey and wasn’t able to attend today but provided a message that I’ll read to you now.

I’d like to close with a quote from someone who knows Percy’s story probably better than anyone. Sam Hawley was a Kingston, Ontario-based writer who wrote an amazing book on Percy’s life called “I Just Ran” published in 2011 by Ronsdale Press here in Vancouver. Sam is now living in Turkey and wasn’t able to attend today but provided a message that I’ll read to you now.

“There are few stories in the history of sports that are so stirring as Percy Williams’, and so worth remembering and celebrating. He is the embodiment of the unlikely hero: an innocent young man barely out of high school, slightly built and shy, who rises from obscurity not just to win a race, not just to become a champion, but to become the best in the world. Twice! If a Hollywood screenwriter were to dream up a fictional story on this theme, it could not be made any more exciting and inspiring than what Percy actually did. His Olympic gold medal performances were so unexpected that he really couldn’t explain it. How can something so magical be explained? When asked what his secret was, Percy just shrugged and said, “I just ran.””

If you would like to watch the entire presentation of Percy’s 1928 Olympic gold medals, please visit the BC Sports Hall of Fame’s Facebook page here: https://www.facebook.com/watch/live/?ref=watch_permalink&v=6353133484719190

Percy’s 1928 Olympic gold medal replicas will remain on public display at the BC Sports Hall of Fame in perpetuity. Currently, they are featured in a large display devoted to Percy located in the Hall of Fame’s Defining Moments Gallery.