Debbie Brill: Breaking Down the Brill Bend – Women’s History Month Feature

October 23, 2021By Jason Beck

Wherever you are right now, take a look at the nearest door in your house or workplace. Look up at the height of it. The average interior door is about six feet eight inches or just over two metres in height. Now imagine trying to jump over that door and clear it. Seems almost impossible, doesn’t it?

eight inches or just over two metres in height. Now imagine trying to jump over that door and clear it. Seems almost impossible, doesn’t it?

Well, Debbie Brill could do it.

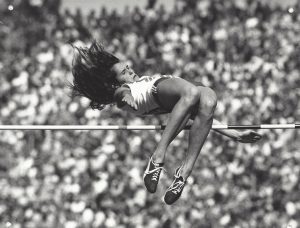

Remarkably, over thirty years since she retired from international high jump competition, Debbie remains the only Canadian woman who could. And she did it using a wholly new technique—‘The Brill Bend’—that she herself created and developed and was later adopted around the world as the predominant style of high jumping. It changed the sport. It fundamentally changed how humans jumped—one of the most basic actions humans have attempted since standing upright on two feet.

Think about that.

Yes, I’ve heard of Dick Fosbury and his more celebrated ‘Fosbury Flop’ but even Fosbury has publicly acknowledged that Debbie Brill is equally deserving of the credit for this high jumping innovation. She was also developing her new ‘backward’ high jumping technique independently at the same time and perhaps even earlier as he developed his own new form. Fosbury’s good fortune was that he had the earlier opportunity to put his new high jumping technique on worldwide display at the 1968 Olympics. But Debbie had a far longer and arguably more successful international jumping career than The Foz.

That fact became crystal clear to me earlier this month—October 8th to be precise—after I was posting the ‘On This Day in BC Sport History’ moment for the day on social media (check out @JasonBeck82 or @BCSportshall on Twitter daily for more):

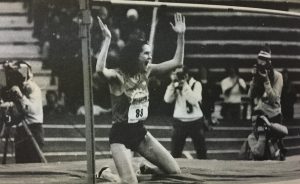

October 8, 1982: Haney’s Debbie Brill wins her second Commonwealth Games gold medal in high jump in Brisbane, Australia–12 years after her first in 1970. Brill leapt 1.88m, the same height as Australian silver medalist Christine Stanton, but recorded fewer missed attempts to take gold.

October 8, 1982: Haney’s Debbie Brill wins her second Commonwealth Games gold medal in high jump in Brisbane, Australia–12 years after her first in 1970. Brill leapt 1.88m, the same height as Australian silver medalist Christine Stanton, but recorded fewer missed attempts to take gold.

When looking into some of Debbie’s other international results from that period in her career, I was shocked to see that she still holds the Canadian national women’s record for high jump in both outdoor (1.98m) and indoor (1.99m) competition, set in 1984 and 1982 respectively. They’re two of the oldest records still standing in Canadian track and field today. And what’s more, those were just the last times that Debbie broke the national records. She has held the Canadian women’s high jump national mark for over 52 years since 1969 when she first broke it at just 16 years old. To provide some context for how remarkable that is, the current men’s national high jump record, held by Derek Drouin, has only stood since 2014 and has been broken numerous times by different jumpers in the past half century.

Debbie Brill was in a class of her own during her career and remains so today, so for Women’s History Month in Canada, let’s celebrate one of Canada’s all-time greatest track and field athletes with special focus on how she pioneered and developed one of the great innovations in sports history.

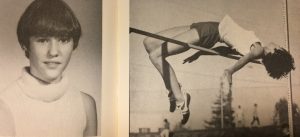

Born in Mission in 1953, as Debbie grew up her family moved around frequently following her father’s various jobs. As such many BC communities lay claim to Debbie as one of their own. Besides Mission/Haney, she was also raised in Ioco, Aldergrove, Fort Langley, and Maple Ridge. It was at age nine in Aldergrove that Debbie first remembers high jumping. While attending the tiny two-room South Otter School, during Sports Day she jumped over a bar into a sandpit, which was common before foam mats were used for landing. Not long after her father took some fishnets and filled them with hunks of foam from a secondhand furniture store and that was her landing mat on the front lawn. Whether it was formal Sports Day competitions at school or informal jumping in the front yard, Debbie always seemed to win right from the beginning.

Born in Mission in 1953, as Debbie grew up her family moved around frequently following her father’s various jobs. As such many BC communities lay claim to Debbie as one of their own. Besides Mission/Haney, she was also raised in Ioco, Aldergrove, Fort Langley, and Maple Ridge. It was at age nine in Aldergrove that Debbie first remembers high jumping. While attending the tiny two-room South Otter School, during Sports Day she jumped over a bar into a sandpit, which was common before foam mats were used for landing. Not long after her father took some fishnets and filled them with hunks of foam from a secondhand furniture store and that was her landing mat on the front lawn. Whether it was formal Sports Day competitions at school or informal jumping in the front yard, Debbie always seemed to win right from the beginning.

“Maybe it was easy for me,” she said in a 1989 interview with the BC Sports Hall of Fame just before her induction that year. “I was very good at it. I was always better than anybody, the boys or the girls.”

Debbie wasn’t using what became known as the ‘Brill Bend’ right away—that evolved over time. Early on, she was using a version of the scissors technique that had her laying back more. That already was different from most jumpers who remained upright whether they were nine years old or 29. Keep in mind, at this time virtually every high jumper anywhere in the world was using some form of either the scissors or perhaps the Western Roll. No one approached the bar with a J-shaped run and flung themselves backward up and over like almost every high jumper at any level today. But as much as Debbie was already adopting her own unique take on accepted high jump form, the biggest difference was in the mindset with how she approached jumping. She wasn’t following a coach’s direction with strict instructions and trying to rigidly mimic textbook form. She was just enjoying the movement of jumping and experimenting and doing so freely.

Debbie wasn’t using what became known as the ‘Brill Bend’ right away—that evolved over time. Early on, she was using a version of the scissors technique that had her laying back more. That already was different from most jumpers who remained upright whether they were nine years old or 29. Keep in mind, at this time virtually every high jumper anywhere in the world was using some form of either the scissors or perhaps the Western Roll. No one approached the bar with a J-shaped run and flung themselves backward up and over like almost every high jumper at any level today. But as much as Debbie was already adopting her own unique take on accepted high jump form, the biggest difference was in the mindset with how she approached jumping. She wasn’t following a coach’s direction with strict instructions and trying to rigidly mimic textbook form. She was just enjoying the movement of jumping and experimenting and doing so freely.

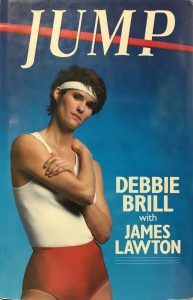

“I worked on instinct,” she said in her 1986 biography Jump written with Welsh sportswriter James Lawton then with the Vancouver Sun. “My instinct told me to run straight at the bar and just fly up into the air.”

Her technique continued to evolve as she explored better ways to approach, take-off, and then get up and over the bar, sometimes with variations on the scissors, other times with a unique take on the Western Roll.

Her technique continued to evolve as she explored better ways to approach, take-off, and then get up and over the bar, sometimes with variations on the scissors, other times with a unique take on the Western Roll.

“I was just trying to get my hips higher to that I could jump higher,” she said in 1989. “I never ever thought about how to go about high jumping, I did it however I could jump high. And that’s what evolved, the backwards jump.”

Debbie was discovered by Pete Swensson, a track coach in the Aldergrove-Langley area, who convinced her parents that she should join the Langley Mustangs track and field club. She began competing in local meets and then in the summer of 1966, a remarkable meeting of perhaps the two greatest high jump innovators in history took place. Barely anyone even noticed they were witnessing a historic high jump summit at the time. That’s because rather than world or Olympic champions one of the innovators was an unknown 13-year-old girl from BC, while the other was an unknown 19-year-old boy from Oregon. The Brill Bend actually first met the Fosbury Flop at a BC vs Oregon co-ed youth track meet in Vancouver. Neither was previously aware of the other. Debbie’s friends came running up to her at the meet at one point saying excitedly, “Hey, it’s amazing—there’s someone else who jumps like you!”

“[It] gave me tremendous relief and encouragement,” she recalled. “When he came up to me, I couldn’t speak. He just spoke to me and I sort of felt, Gosh! Wow!…”

“[It] gave me tremendous relief and encouragement,” she recalled. “When he came up to me, I couldn’t speak. He just spoke to me and I sort of felt, Gosh! Wow!…”

Writer Bob Welch wrote about this unexpected meeting in Fosbury’s 2018 biography The Wizard of Foz:

“The meeting surprised Fosbury, too. In a world that saw Brill and Fosbury as different, the two were bonded, if even for a few hours, by their sameness. When they left to go their separate ways, neither foresaw a day when they would blend in like everyone else—not because the two of them would conform to the world, but because the world would conform to them.”

In January 1967 Debbie competed at one of her first senior meets away from home, travelling on her own to Kelowna. Despite extreme shyness around all the older unfamiliar athletes and fighting off freezing temperatures in an unheated indoor arena, she won the competition jumping 1.50m, about 8cm higher than she’d ever jumped before. Despite the unfamiliarity of everything for her, she found comfort in the one thing she knew: jumping.

“So many times in my life it would be like this,” she said. “The confusion just fell away. There was the bar and here was me. The challenge was simple enough. Just get over the goddamned thing, girl, and do it naturally.”

It was around this time that Swensson coined the name for Debbie’s technique as the Brill Bend. Her style and performance began attracting attention in wider circles. Over the next six months, her technique evolved to an even more pronounced backwards form and it just kept evolving from there.

“I sometimes look at my technique of early 1967 on some grainy film,” she said in 1986. “It’s the strangest sensation. It is just possible to see the outline of my present style, but it is very blurred.”

By 1968, Debbie had set the BC provincial record of 5 feet 6 inches and came in second at the Canadian national championships behind the great Diane Jones-Konihowski. Debbie was named to the Canadian national team and went to Europe to compete in several meets. There, in front of large crowds in massive stadiums in Sweden, Norway, and Britain she learned the hard way that people can be brutally mean when confronted by something new they don’t understand. No one had ever seen a person high jump backwards in Europe. Debbie Brill was a shy 15-year-old on a foreign continent for the first time and thousands of people were jeering and ridiculing her.

By 1968, Debbie had set the BC provincial record of 5 feet 6 inches and came in second at the Canadian national championships behind the great Diane Jones-Konihowski. Debbie was named to the Canadian national team and went to Europe to compete in several meets. There, in front of large crowds in massive stadiums in Sweden, Norway, and Britain she learned the hard way that people can be brutally mean when confronted by something new they don’t understand. No one had ever seen a person high jump backwards in Europe. Debbie Brill was a shy 15-year-old on a foreign continent for the first time and thousands of people were jeering and ridiculing her.

“This huge Olympic stadium in Oslo was filled with people and I’d only jumped in front of friends and family,” she recalled. “So I was just scared to death and it seemed like everybody that could see me jumping in the end where the high jump was, was laughing. They just thought it was hysterical, this skinny little kid going backward. So I fell apart and came last.”

But she didn’t give up and continued to refine her unorthodox technique. Back in the comforts of home, Debbie pulled herself together and jumped a personal best 5 feet 7½ inches, which was a world age class record and met the Olympic qualifying standard. But Canadian officials chose not to send any women in the high jump to the Olympics and so only Fosbury was able to show the new way of high jumping to the world.

But if Fosbury opened the door a crack, Debbie and others who followed blasted that door wide open. By the next Olympics in 1972, when Debbie was selected to compete for Canada in Munich, there were more jumpers competing using the Brill/Fosbury reverse technique than any other. And as Debbie and other top jumpers pushed the bar of possibility higher and higher with the new technique, it quickly made all other forms like the scissors and Western Roll obsolete. For decades now, if you want to compete and win at any level of high jump anywhere in the world, it’s almost a certainty that you must employ the Brill Bend/Fosbury Flop to have any realistic chance.

But if Fosbury opened the door a crack, Debbie and others who followed blasted that door wide open. By the next Olympics in 1972, when Debbie was selected to compete for Canada in Munich, there were more jumpers competing using the Brill/Fosbury reverse technique than any other. And as Debbie and other top jumpers pushed the bar of possibility higher and higher with the new technique, it quickly made all other forms like the scissors and Western Roll obsolete. For decades now, if you want to compete and win at any level of high jump anywhere in the world, it’s almost a certainty that you must employ the Brill Bend/Fosbury Flop to have any realistic chance.

While Fosbury reached the pinnacle of high jump with an Olympic gold medal-winning performance in 1968 and quickly departed the world scene, Debbie’s climb to the top was more gradual and her stay there much more lasting.

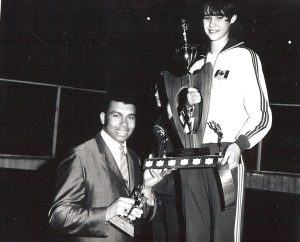

Her first major international victory came in 1969 winning the Pacific Games meet in Japan. Working with new coach Lionel Pugh based out of UBC, in 1970 while still only 16 years old she became the first North American woman to clear 6 feet and only the 11th in the world.

“I walked into a void,” Debbie told Wendy Long in her 1995 book Celebrating Excellence. “There was nobody in North America jumping more than 5’9” when I started and that was so low. I just flew right by it. I didn’t even realize it, but within three years of jumping I was already in the top few of the world, even though I didn’t know what that meant.”

“I walked into a void,” Debbie told Wendy Long in her 1995 book Celebrating Excellence. “There was nobody in North America jumping more than 5’9” when I started and that was so low. I just flew right by it. I didn’t even realize it, but within three years of jumping I was already in the top few of the world, even though I didn’t know what that meant.”

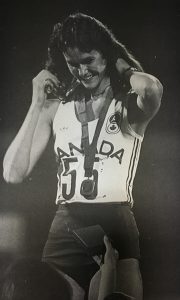

Debbie won her first Commonwealth Games gold medal that same year in 1970. She later added a silver at the 1978 Commonwealth Games, a second gold in 1982, and finished fifth in 1986. She represented Canada at three Olympic Games (1972, 1976, 1984) finishing in the top-ten twice (8th in 1972 and 5th in 1984). Her best chance for an Olympic medal may have been taken from her during the 1980 Olympic boycott. She was ranked number one in the world in 1979 going into that Olympic year. She took gold at the 1971 Pan American Games, finished 4th in 1975, and rebounded to take silver in 1979. She would win competitions at dozens of major international meets around the world. From 1970 to 1985, she was ranked in the Track and Field News world top-ten 12 times. She won the Canadian national high jump championship 11 times in her career, to go along with two US national titles and one UK title.

Off the top of this article we mentioned Debbie’s 1.99m Canadian indoor record set in 1982. What we didn’t mention was that this was also a world record and she set it just months after having her first son Neil. In the years since I’ve heard numerous women say how inspired they were by this accomplishment coming at a time when many still felt that the athletic careers of women were over after having children. Once again, Debbie Brill changed the way people thought and reshaped our idea of what was possible.

Even after retiring from open competition in 1988 and taking a long break, Debbie returned to Masters competition in the 1990s and there too she re-wrote the record book. In 1999 she set a world Masters record in the 45+ age bracket with a jump of 1.76m. Five years later, she set the 50+ world Masters record with a jump of 1.60m.

Even after retiring from open competition in 1988 and taking a long break, Debbie returned to Masters competition in the 1990s and there too she re-wrote the record book. In 1999 she set a world Masters record in the 45+ age bracket with a jump of 1.76m. Five years later, she set the 50+ world Masters record with a jump of 1.60m.

Even if her resume is chock full of championships, medals, and records, that was never why Debbie first jumped and why she continued jumping for decades.

“For me, it wasn’t just high jumping to win medals,” she said. “It was always much more. It was the kind of freedom you get, a sense of freedom of movement and expression. You have to move smoothly, in one piece, and have all parts working together. So when you put it all together it’s an extraordinary feeling, the most wonderful feeling.”

Why walk when you can run? And why just jump when you can soar even higher?

Debbie Brill showed us the answer.