Alex Stieda: ‘Le Maillot Jaune’ (The Yellow Jersey) – 2020 Inductee Spotlight

April 8, 2020By Jason Beck

Going into the second day of the 1986 Tour de France, Alex Stieda had a plan.

The 25-year-old cyclist from Coquitlam was riding in his first-ever Tour with the 7-Eleven Team and had put himself into good position in the previous day’s prologue, a 4.6km individual time trial, finishing in 21st place, just 12 seconds behind early race leader France’s Thierry Marie.

“I just thought if I could just get away and win some of the time bonuses,” remembered Alex in a recent phone interview from his home in Edmonton, “then I could move myself up and maybe go into the overall lead. It was a far-reaching goal, but possible.”

As unlikely as snatching the Tour’s famed yellow leader’s jersey (‘le maillot jaune’) may have seemed—Alex was only eight years removed from taking up cycling seriously and at this time no North American rider had ever held the overall Tour de France lead—it somehow made sense in his mind. He just needed to figure out a way to slip away from the peloton of cunning, veteran riders who’d seen it all on the bike. Not an easy task. It came to him midway through Stage 1 of the race, a short 85km leg from Nanterre to Sceaux on the outskirts of Paris. The main group was just rolling along not moving particularly fast. Alex worked his way to near the front and thought ‘why not try bluffing these guys with a pee break?’

You read that right. A pee break. During the Tour de France. The crazy thing is it worked.

“I didn’t actually attack that hard but I went just that much faster than the peloton, so I could get away from them,” he said. “Normally when you do that, you’re going up the road so you can stop and pee and the riders let you go. Honestly, it was that type of attack. I didn’t go crazy hard. I just kind of rolled up the road and stayed to the left as if I was going to stop to have a nature break.”

“I didn’t actually attack that hard but I went just that much faster than the peloton, so I could get away from them,” he said. “Normally when you do that, you’re going up the road so you can stop and pee and the riders let you go. Honestly, it was that type of attack. I didn’t go crazy hard. I just kind of rolled up the road and stayed to the left as if I was going to stop to have a nature break.”

Don’t believe it? You can watch video of Alex’s breakaway on Youtube here: https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=z8tfwG8Wjxc (at the 0:58 mark, he makes his move breaking from the pack).

When no one gave chase, he decided the time was now to use the windy French roads to his advantage.

“I looked back and as soon as I saw I was out of sight of the peloton, then I went into maximum effort mode,” he recalled. “And by then it was too late for the peloton to react because I was out of sight and they didn’t see that I was going full gas. It’s those kind of mind games that play into the race.”

At that time on the Tour, there were four 12-second sprint time bonuses awarded during this single stage, something that’s not done today. So by staying in front he banked these knowing that if he was caught by the pack and he could hang on, he may have a shot at the Tour’s overall lead.

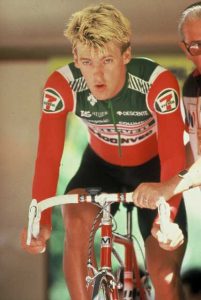

He also was wearing another advantage that day: a full-body one-piece lycra skinsuit or ‘speed suit’ as they’re known today. Everybody wears them now, but back then most just wore a jersey and shorts.

“I knew that the skinsuit was more aerodynamic and had anecdotal evidence that it felt faster because we wore them in shorter criterium events like the Gastown Grand Prix,” he explained. “But back then no one realized that. That was a thought in my mind that I could get away and be faster that way. I was sort of a pioneer, if you will, in that realm trying different things. If the European guys had worn a skinsuit in a road race, they would be laughed at.”

No one was laughing at the young Canadian’s red, green, and white 7-Eleven skinsuit as he kept the tempo high, thighs pounding the pedals furiously, head down, eyes intensely trained on the road ahead. Soon he had built nearly a two-minute lead on the trailing pack. It would have been nearly impossible to maintain that kind of blistering pace though and gradually a small group of five experienced riders began chipping away at his lead until they reeled Alex in and he was caught. The great Australian cyclist Phil Anderson, who’d finished fifth overall on the 1985 Tour, gave Alex a friendly pat of respect as they sped by him. But Alex dug deep and latched onto this group, refusing to give in. He ended up finishing the stage in fifth place, nine seconds behind the winner Pol Verschuere from Belgium.

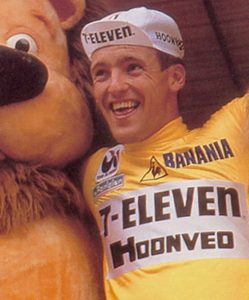

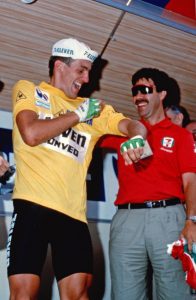

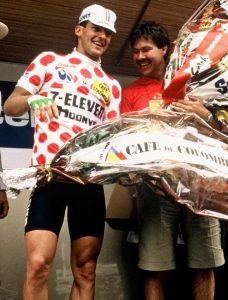

And with that, Alex had made history as the first North American to hold the overall lead in the Tour de France, eight seconds over the next closest competitor. Including the coveted yellow leader’s jersey, he actually won five different jerseys (of six available to be won) on the day. The others included: the polka dot jersey as ‘king of the mountains’; the white jersey as top young rider; the multi-coloured jersey as the combination classification leader; and the red jersey as the intermediate sprints leader.

And with that, Alex had made history as the first North American to hold the overall lead in the Tour de France, eight seconds over the next closest competitor. Including the coveted yellow leader’s jersey, he actually won five different jerseys (of six available to be won) on the day. The others included: the polka dot jersey as ‘king of the mountains’; the white jersey as top young rider; the multi-coloured jersey as the combination classification leader; and the red jersey as the intermediate sprints leader.

“Winning the yellow jersey, I could never have predicted that!” he laughed. “It was just exhilarating. It’s the holy grail all cyclists seek and I had touched it.”

Suddenly he was the toast of the cycling and entire sports world, images of him wearing one of the most identifiable jerseys in all of sport beamed around the globe.

“I was in a daze really,” he said. “So many things were happening at the same time. On the podium. Off the podium. On the podium. Off the podium. Pictures. Pictures. Pictures.”

As crazy as it might sound for a young Canadian cyclist from Coquitlam who preferred hockey growing up to lead the Tour de France, what was even crazier was without even really getting a chance to celebrate, just a few hours later that afternoon he and his teammates were forced back out on their bikes for the Tour’s second stage, a 56km team time trial. The Tour today limits racing to one stage a day. Alex would surely have benefitted from the extra rest that afforded.

As it was, he had expended so much in taking the yellow jersey in the earlier stage that he struggled mightily in the team time trial, barely finishing within the allowable time limit and losing the overall Tour lead and the coveted yellow jersey. He and his 7-Eleven teammates, jubilant and ecstatic just hours earlier, were now crushed and shattered.

Such is the rollercoaster of emotions that comes with the world’s toughest and most prestigious bicycle race. Alex did manage to hold onto the polka dot jersey until Stage 6 and his 7-Eleven teammate Davis Phinney rebounded nicely to claim the win in Stage 3. But for Alex from that point on in the race, it was about survival.

“The next day, one of the older Dutch riders, Gerrie Knetemann on the PDM-Concorde Team, rode up to me and said, ‘You know Alex, it’s so important that you won the yellow. But to prove that you are worthy of wearing the yellow jersey, you have to finish the Tour de France.’ To prove it wasn’t a fluke. I decided, ‘Okay Gerrie, you’re on.’ So I was basically his lap dog for the whole Tour de France. Anytime we came to a mountain climb I rode at his pace, so that I could get to the finish without blowing up or expending too much energy. It was about getting through each stage, each day and finishing the race, surviving. In the end only five of the ten riders from our team, who started, finished.”

“The next day, one of the older Dutch riders, Gerrie Knetemann on the PDM-Concorde Team, rode up to me and said, ‘You know Alex, it’s so important that you won the yellow. But to prove that you are worthy of wearing the yellow jersey, you have to finish the Tour de France.’ To prove it wasn’t a fluke. I decided, ‘Okay Gerrie, you’re on.’ So I was basically his lap dog for the whole Tour de France. Anytime we came to a mountain climb I rode at his pace, so that I could get to the finish without blowing up or expending too much energy. It was about getting through each stage, each day and finishing the race, surviving. In the end only five of the ten riders from our team, who started, finished.”

The struggle was worth it. Alex ended up finishing 120th overall out of 210 starters, two hours and 19 minutes behind overall winner Greg LeMond from the USA, who became the first non-European to win the Tour. Beyond wearing the yellow jersey, something no one can ever take away from him, one other moment stands out.

“There’s nothing like riding on the Champs–Élysées as a finisher of the Tour,” he says today, the awe unmistakable in his voice. “That’s an incredible moment. And to win the yellow jersey, to pull that off? That was craaa—zzzy! The odds of that happening are pretty remote. If you think about it, I’d only really started biking seriously in 1978. Incredible.”

Going back even further, Alex Stieda’s rise to the pinnacle of cycling is as surprising as the Coquitlam hills he battled at the end of each ride are steep. Born in Belleville, Ontario, Alex’s family followed his dad’s construction work right across the country—to Winnipeg, Penticton, and finally Coquitlam. His dad built their house by hand himself on Gatensbury Street near Como Lake in the late 1960s.

Alex was your average skinny kid who played soccer and was put into figure skating because his sisters were already in it. That proved an unexpected advantage at age 11 when his parents finally relented to years of Alex pleading to play hockey; he immediately was one of the best skaters on his team.

Alex played hockey for several years when at age 15 in 1976 he began looking for a way to keep in shape during the summer offseason. He decided to ride his bike.

“I bought a ten-speed from someone at my high school for 20 bucks and fixed it up,” he recalled. “I painted it myself with a brush.”

He began riding around the Lower Mainland, his parents even allowing him to bike to Tsawwassen, catch the ferry, and ride over to the Gulf Islands for overnight camping trips.

“I still can’t believe to this day that they let me do that!” he mused.

Living at the top of the hill in Coquitlam presented a unique challenge to an aspiring cyclist. No matter which route you took home, at the end of your ride you were forced to battle one of several daunting hills—Thermal Drive, Blue Mountain Street and others. The power and endurance that later characterized Alex as a standout international rider has its origins in these early climbs.

“If you felt strong you’d go up one of the steeper hills, but if you were at the end of your rope at the end of a 100-mile ride, you’d just try to find the easiest hill,” he recalled. “But more often than not, I was so shattered I’d have to go up one or two blocks and then pull off to the side street, do a couple turns to recover, and then go up another couple of blocks, pull off to recover, and go up again. Make my way up the hill to get home. Those were early days, just trying to figure life out and figure out how to ride the bike properly.”

In the late 1970s, the Lower Mainland’s cycling community was small and tight-knit. You just didn’t see people training on a road bike out on the roads that often and certainly none of the pelotons of weekend riders you see regularly on certain routes today. “In those days, after a couple of years, if I saw someone on a ten-speed, I knew who it was!”

A series of random coincidences pushed Alex deeper into the sport. His neighbor two houses down in Coquitlam was a man named Harold Bridge, whose wife Joan was the president of Cycling BC at the time. Harold was a British randonneur cyclist (sometimes called marathon cycling) who enjoyed long rides of several hundred kilometers at a slow pace. Harold took Alex out on rides and taught him the basics and rules of the road.

Around the same time, Alex discovered his grandfather, who grew up in Britain, had been a racing cyclist in the 1950s. Photos and stories of his grandfather’s career began to open up a new world he was previously unaware of.

Harold suggested to Alex that he try racing in a weekly ten-mile time trial out on the roads around UBC put on by a local masters cycling club. Alex rode his bike all the way out there from Coquitlam after school, did the time trial, and rode all the way home. “I didn’t know any better,” he laughed. “Crazy.”

He did well enough in the time trial that Harold then pointed him in the direction of a short-lap criterium race in Ladner. Alex ended up winning the beginner’s category. More importantly, he met a few other junior riders who were training seriously. Soon he was going out on organized rides with other juniors all over the Lower Mainland, from Vancouver to Mission and as far south as 0 Avenue in south Surrey. Not long after, he was biking to a job at Larry Ruble’s Cycle Shop in Maple Ridge where he earned enough money to buy a new Nishiki Landau.

“One thing led to another to another to another,” Alex mused. And it only continued.

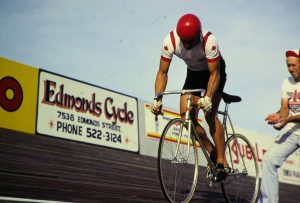

In 1977, Alex was introduced to track cycling at China Creek Park, the old steeply-banked outdoor track made of yellow cedar, built for the 1954 British Empire and Commonwealth Games and located where Vancouver Community College is today. There he met Barry ‘Baz’ Lycett, who was the coach at the track of junior riders and encouraged Alex to join his group.

“I was pretty rough around the edges,” Alex laughed. “I didn’t have any of the tactical abilities or know the nuances about track riding, but they yelled at me a few times and I learned. Pretty soon I was in the mix, sticking my head in there and sprinting with these guys, getting stronger all the time.”

Many of the junior riders Alex joined proved to be cycling ‘lifers’ and are still active today. They included Bruce Spicer (current partner in Brodie Bicycles), Brian Green (helps run the Red Truck Racing cycling team), and Neil Davies (runs Jubilee Cycle).

Baz took his cadre of young cyclists racing all over the Pacific Northwest. On Fridays after school he’d pick them all up in his Volvo station wagon, load their bikes in the back, and they’d drive down to Seattle to race at Marymoor. Sometimes when Alex was a little older, after racing on the track on Friday nights, they’d also bring their road bikes and enter a race in Seattle or Portland on Saturday or Sunday. All of this was done with a sense of adventure.

“It was just what’s happening next weekend? Okay, let’s go! This is fun. This is adventurous. Our BC team was just palling around, racing, winning, chasing girls, and having a ball. It was such a great time. Those were some of the best times I’ve had as a bike racer.”

“It was just what’s happening next weekend? Okay, let’s go! This is fun. This is adventurous. Our BC team was just palling around, racing, winning, chasing girls, and having a ball. It was such a great time. Those were some of the best times I’ve had as a bike racer.”

It was also around this time that Alex met an older cyclist who became a mentor. Ron Hayman, a two-time Canadian Olympian, was one of the first Canadian cyclists to race professionally in Europe in the late 1970s. In the winter, he’d join Baz’s training group and Alex witnessed up close how hard a professional had to work to make it overseas.

“We were just amazed at how hard he was training and pushing himself in these rides. He would tell us the races are always hard, but the harder you train, the better the race will feel. He really was someone we all looked up to.”

By 1978, Alex was on the BC provincial junior team and began turning heads. All those thigh tenderizing hill climbs back home in Coquitlam were paying off. At the Canadian junior national championships that year, he cleaned up winning just about every sprint and distance event possible. The fact he won both sprint and endurance events, something that rarely happens—usually it’s one or the other—immediately thrust him on the national radar.

Next was a trip to the UCI junior world track championships in 1979 in Buenos Aires, Argentina. Alex advanced to the quarterfinals in the individual pursuit and was paired against the same man who would later win the 1986 Tour de France—Greg LeMond. “We battled it out for nine laps and he ended up juussstt beating me by a hair to move on to the semifinals. But that was like, ‘This is cool! I feel like I’m right there, you know?’” LeMond went on to claim silver in the event. Years later, Alex gained a form of revenge over the American legend beating LeMond in a sprint to the finish of a stage of the Coors Classic in San Francisco.

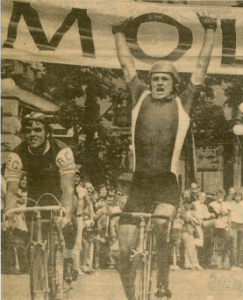

1980 proved a pivotal year for Alex. He won the Tour de l’Abitibi in Quebec, a junior stage race featuring some of the best young riders in North America. He also won his first Gastown Grand Prix in Vancouver, rebounding from a crash with a pedestrian the previous year that mangled his bike and ended his race. Winning the 1980 edition was a complete shock and showed how far he’d come, but also how far he still had to go. “I was wearing this green skinsuit that my mom had made,” he chuckled. “I had both hands up and I was screaming across the finish line. That was one of the catalysts to the rest of my career.”

Alex stayed close with Ron Hayman, picking up bits of cycling wisdom and following his direction on where to take his career next. They even worked together for Roto Rooter—“to help pay for our habit of being a bike racer”—as many local cyclists did at that time. The owner of the company’s Lower Mainland franchise was Dave Mendenhall, a cycling photographer and sponsor of the Carlton-Roto-Rooter cycling team. Little did Vancouver-area residents know but their clogged drains and leaky pipes were often tended to by some of Canada’s best cyclists of the era.

It was Hayman that brought Alex over to Roger Sumner’s house one day in 1980. Sumner, a dentist, was the founder of the Gastown Grand Prix and one of the best developers of young cycling talent in Canada. Alex became another up-and-comer who benefitted from Sumner’s influence. Hayman and Sumner felt the next step for Alex was to go race in Belgium in 1981 and learn what European cycling was all about.

His family couldn’t afford the plane ticket, so Coquitlam city council awarded him a $500 grant for airfare that got him as far as Ottawa. From there the Canadian Cycling Association managed to get him on a Department of National Defense flight to Laar, Germany. With a clunky fiberglass bike box his dad made for him and not understanding a word of German, Alex hitched a ride to the nearby train station, managed to transfer trains in Frankfurt, arrived in Ghent, Belgium in the middle of the night, and somehow clunked and clattered his bike box down the maze of dimly-lit cobblestone streets to the building where Hayman’s friend Luc Eysermans had a place for Alex to stay. This, we should point out, was all arranged beforehand by handwritten letters in the days before cell phones and computers. Alex, only 20, had never been to Europe, had never met Luc before, but somehow it all worked out. And he learned a ton.

His family couldn’t afford the plane ticket, so Coquitlam city council awarded him a $500 grant for airfare that got him as far as Ottawa. From there the Canadian Cycling Association managed to get him on a Department of National Defense flight to Laar, Germany. With a clunky fiberglass bike box his dad made for him and not understanding a word of German, Alex hitched a ride to the nearby train station, managed to transfer trains in Frankfurt, arrived in Ghent, Belgium in the middle of the night, and somehow clunked and clattered his bike box down the maze of dimly-lit cobblestone streets to the building where Hayman’s friend Luc Eysermans had a place for Alex to stay. This, we should point out, was all arranged beforehand by handwritten letters in the days before cell phones and computers. Alex, only 20, had never been to Europe, had never met Luc before, but somehow it all worked out. And he learned a ton.

“I spent two months riding my bike to races with a backpack on, signing up in a café or a bar, renting a number and paying the entry fee, usually a few francs,” he recalled fondly. “I ended up winning four races against a bunch of really strong local Belgian riders and I got the hang of it.”

That same year, he went to the UCI track cycling world championships in Brno, Czechoslovakia and just missed out on a top-three finish in the individual pursuit. Alex’s performances in Europe earned an invite to race for the fledgling 7-Eleven team in New York and he became a full team member in 1982. Hayman, also a member of 7-Eleven, ensured Alex felt welcome from his very first race with the American team, a criterium in the parking lot of Caesars Palace in Las Vegas.

“They actually put plywood ramps up and down each speed bump. It was super hokey. They wouldn’t host a race like that today.”

Alex broke away with Hayman near the finish. Hayman turned to him and said, “It’s your first race on the team, you take the win.” Alex gladly sprinted to victory and remained a member of the 7-Eleven team for the remainder of the decade.

The accomplishments came fast after that:

- bronze medal in individual pursuit at the 1982 Commonwealth Games in Brisbane, Australia

- bronze medal in individual pursuit at the 1983 Universiade in Edmonton

- competing for Canada at the 1984 Olympics in Los Angeles

- three-time Canadian senior national track cycling champion

- 1984 Gastown Grand Prix champion

- two-time overall winner of the Tour of Texas (1988, 1989)

- two-time winner of the Tour de White Rock (1989, 1991)

He was racing close to a 100 days a year, on the bike around ten months out of twelve. It was as exciting as it was grueling.

He was racing close to a 100 days a year, on the bike around ten months out of twelve. It was as exciting as it was grueling.

In 1986 Alex turned pro with the 7-Eleven team, which opened the door for his debut at the Tour de France that year and his brush with cycling immortality.

He continued racing professionally until retiring in 1992. Married to wife Samantha, with one child already and another on the way, he took a sales job with the Softride bike company in Bellingham. Later Alex and his family moved to Edmonton, where they live today. He works in IT services and still cycles regularly, participating in many Gran Fondo style races and some mountain biking, including the Cape Epic eight-day stage race in South Africa and the Trans-Rockies Classic with his son.

“It was just so fun, me in my fifties racing with my son in his twenties. Magic!”

He considers his biggest accomplishment the founding and organizing of the Tour of Alberta stage race, which ran for five years from 2013-17.

Cycling remains at the heart of everything Alex does and who he is.

“Any time I’m pedaling, that’s all the matters,” he says. “That feeling of flying. It harkens back to my days growing up in Coquitlam. Feeling that wind in your face—back then wind in your hair!—but that’s something really special. So whenever I’m pedaling my bike, I’m happy.”

Alex Stieda will be inducted into the BC Sports Hall of Fame in the Athlete category as part of the Class of 2020 Induction.